|

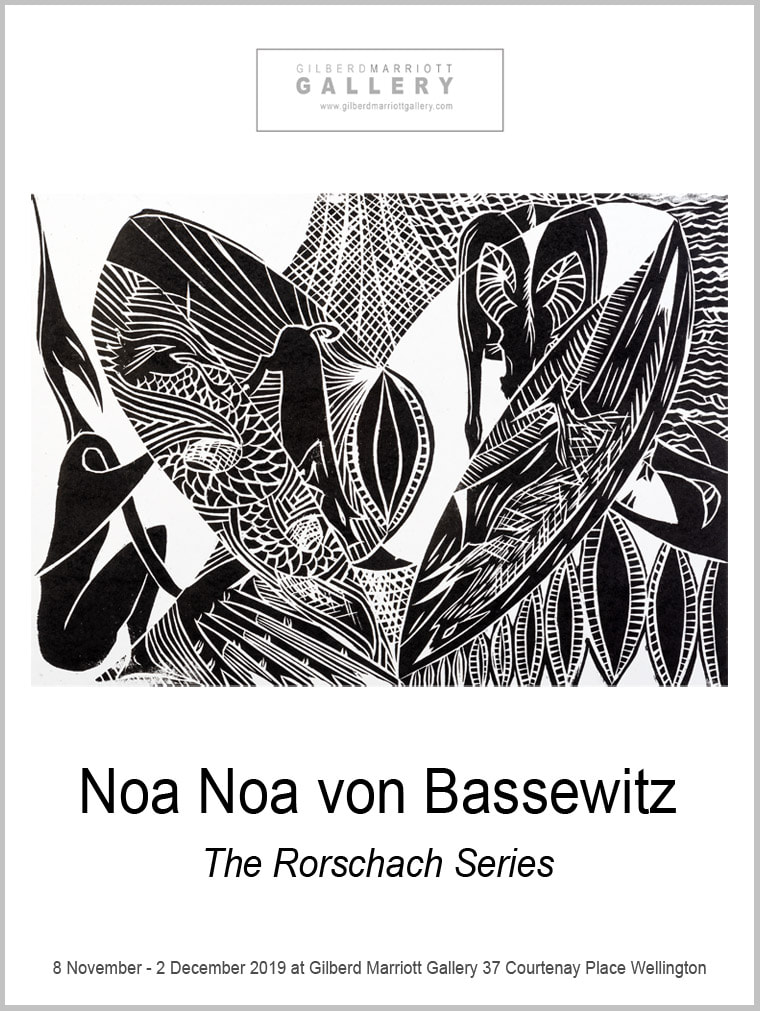

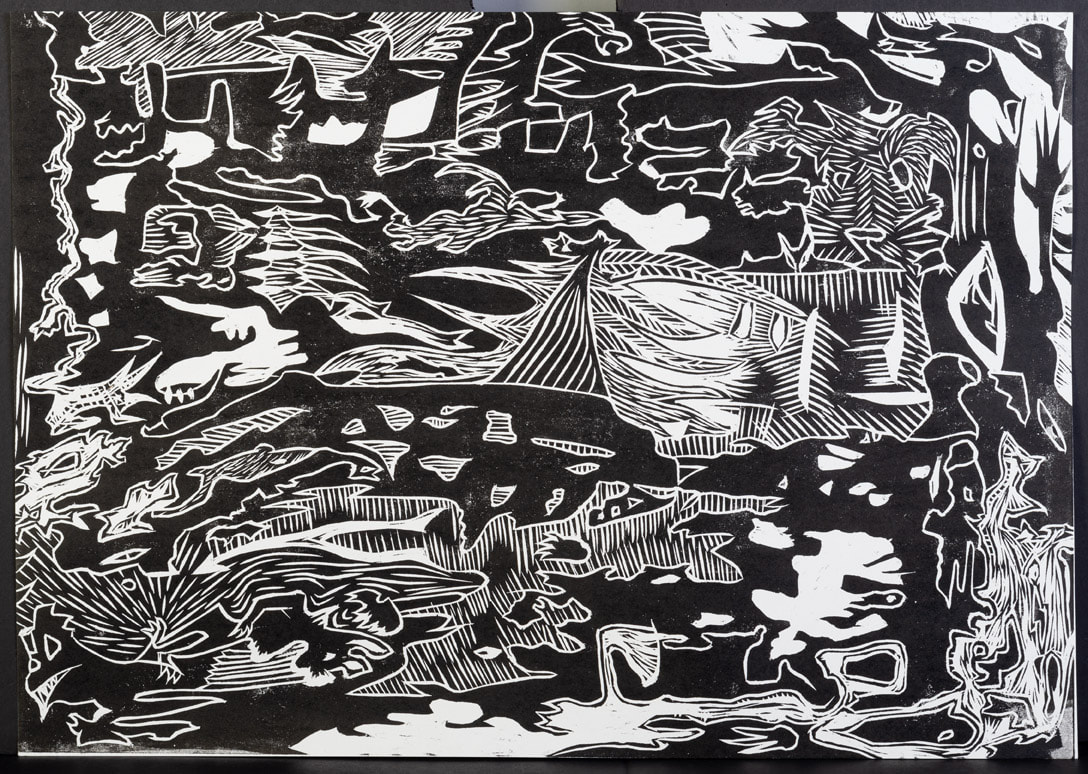

Noa Noa von Bassewitz's first exhibition of woodblock prints at Gilberd Marriott Gallery - The Rorschach Series' - runs from 8th November to 2nd December in rooms 3 and 4. The exhibition opening function will be on Thursday 14th November, 5pm-7pm (so as not to clash with a Photospace Gallery opening on the 7th). Artist info: Noa Noa Von Bassewitz is a Wellington based print maker of German and Maori extraction. Her fascination with the medium of print began 24 years ago when she attended a print making course run by Jenny Dolezel at Elam art school. Wood block prints are her chosen medium for expression. Her art works are often raw and filled with both personal and pacific symbolism and a rich cast of ever evolving characters. Her work has been featured in Takahe and in Asian Art Review in 2013 (see below). An anthropologist and teacher by training, Noa Noa has also worked producing educational resources, as a sexuality educator, and a freelance illustrator. After an elongated hiatus, Noa Noa is back working full-time as an artist as well as raising her four fabulous boys and managing a loud, hungry and highly creative household with her Austrian husband and two crazy cats and a tiny black wolf dog. The Rorschach Series The Rorschach Series explores one of the artist’s core themes —the subconscious— in particular its role in her art making. The Rorschach Test* which uses evocative inkblots to unearth the workings of a person’s subconscious mind, has been used here as a way to describe the artist’s creative process. Two of Noa Noa’s print series “Rona and the Moon” (2009) and “The Imperfect Pull” (2018) have utilised the moon as an anchoring object and metaphorical symbol for the subconscious; in this new series the subconscious becomes the driving force for the creation of the prints. The theme is the process. In clearing her mind, the artist can be guided by the medium, emotion and the synergy created by not attaching to an outcome. The Rorschach Series does not refer to the look of the finished print, there are no cloudy ink blots in sight, there is nothing that could look like a bat with outstretched wings or a kissing couple, it is is the process that is reminiscent of the Rorschach Test, not the end result. The prints are presented as completed “tests”, glimpses into the artist’s inner machinations. Like the personality test after which they have been named, these prints are a first impulse / an interpretation and an insight into the mind of the artist. The artist draws from a rich cast of creatures, in settings that are evocative of joy or curiosity, strife and yearning, water, wood, other worlds beneath the surface. Her Maori heritage connects her with the Pacific and the textures and patterns she uses give her work a strong sense of place within New Zealand. The works, although presented as completed tests, are still only suggestive of forms, the beings are like those in a dream: certain features are clear and others are lost by our inatention. Like the original tests, the prints have the potential to be interpreted in many ways, viewers are naturally invited to see what they would like to see in the prints as the forms are not pre-defined. Whales play and birds talk, the wolf is lost and questioning within the woods, animals flee like ghosts from the page, pigs and serpents and horned horses, livestock, cats and a giant dog’s head all twist together to form half complete anthropomorphic landscapes. There is a feeling of water, of masculinity, of escape and domesticity intermingled. *The Rorschach Test is a psychological test in which subjects' perceptions of inkblots are recorded and then analysed using psychological interpretation, complex algorithms, or both. Some psychologists use this test to examine a person's personality characteristics and emotional functioning. It has been employed to detect underlying issues, especially in cases where patients are reluctant to describe their thinking processes openly.The test is named after its creator, Swiss psychologist Hermann Rorschach. The images themselves are only one component of the test, whose focus is the analysis of the perception of the images. The following article was scanned from a magazine and made into a Word document. Illustrations were not included, sorry.

Shifting Connections By Cassandra Fusco ASIAN ART NEWS SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2013 pp71–73. Among the riches of contemporary New Zealand art is outstanding woodblock printing. Noa Noa von Bassewitz is one of New Zealand's most important print artists. Her oeuvre is filled with singular artistic statements and ideas that speak across cultural boundaries. The prolific New Zealand artist Noa Noa von Bassewitz describes herself as "a happy chameleon; being many things to many people." And much of this in forms her art making and publications but so, too, does the reality that she is of Maori and German descent. She draws intuitively and deeply from both cultures for her art, one that also gains much strength from the fact that even as a child she was "drawn to and could identify with images of strong, dark women." She also says "the windy fingers of Tawhirimatea (the Maori god of winds and storms) have wrapped themselves around my existence and helped shape who I am. Windblown by a whirlwind mother and South Seasdreaming father, I grew up in Wellington, the windiest of cities this side of the equator, talking in two tongues like a fish of two waters." And her name, "meaning 'fragrant scent' in Tahitian, comes from Noa Noa: The Tahiti Journal of Paul Gauguin (1894- 1900)," further enhances the magic that is part of her personality and her art. Von Bassewitz, who was born in 1975, is a mid-career artist with a prolific body of prints and publications to her credit.1 Her woodblock prints, incised with myth and metaphor, pay little attention to classical perspective and boldly eliminate subtle gradations of color, thereby dispensing with the two most characteristic principles of much postRenaissance art. Instead, von Bassewitz 's compositions-of stark forms, strong colors and rhythmic patterns and reflecting much of her rich bi-cultural upbringing offer space and pause beyond naturalistic representation. Trained in anthropology and design in Dunedin and in Auckland and also as an artist and a writer, von Bassewitz explores and "metaphorically translates cultures in paintings, ink drawings, paper creations, line drawings, screen, intaglio, wood prints, and illustrations." Yet even with an academic background von Bassewitz says that she learned, at an early age, the intricacies of printing from her mother, who was an art teacher. Subsequently von Bassewitz studied various media with New Zealand artist, Jenny Doležel, at Elam summer school, the University of Auckland. During this time the artist was particularly drawn to lithography and various other chemical, biting techniques, but she eventually found woodblock printmaking to be the most satisfying medium for her. "By virtue of its time-consuming incising and labor-intensive processes, woodblock slowed me down," says von Bassewitz. "Whereas I had little interest in reworking paintings, I found that with print, after the initial creative act, I enjoyed exploring further, making a multitude of new appearances through colors and paper changes and printing pressure, such as seen in the Taniwha works of the past several years." In Maori culture, taniwha are supernatural creatures, similar in significance and appearance to serpents and dragons in other traditions. Taniwha belong to the realm of te ira atua (the godly or mythical aspect) and legend has it that they arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand with the early voyaging canoes.2 Taniwha may take the form of giant, spike-spined lizards, with or without wings. Or they may appear as reptile-like sea creatures, sharks or whales, or even great logs in rivers. They can be either male or female, are deft shape-changers and are said to hide in the ocean, rivers, lakes, or caves. While some taniwha are believed to be aggressive and mischievous, others are credited as being kaitiaki (guardians or protectors) for an iwi (tribe) who, in turn, offer them gifts such as karakia (a chant or spell). The large and small taniwha in von Bassewitz's Oh Mama (2009) invoke this protective aspect with a gentle economy by comparison with the amorous intertwining entities of Moon Lovers, Taken in the Moonlight, and By the light of the Moon (all 2009) as well as the everchanging entities of Cavorting Taniwha (2009) Both Moon Lovers and By the light of the Moonlight explore the coming together of the male and the female principle, a little tentatively and then in complete connection in Moon Lovers where the male and female taniwha intertwine, reminiscent of birds (such as swans) that mate for life. The lines surrounding these taniwha ripple. As in traditional Maori weaves, they are symbolic histories, lines of connection. They do not so much mark out forms and space in a descriptive, dimensional sense, but rather, indicate processes beyond the visible image. Taniwha and Moon (2009) was the first print in the series, which features the symbolic meeting of herself the main protagonist, gleeful and strong, a complete form in her natural element. The moon has important symbolic meaning for Maori and is strongly associated with women and the menstrual cycle, as in many cultures. The moon as Hineteiwaiwa is associated with fertility and the cycle of life. The moon’s cycle has also been linked to the opening and closing of a portal through which departed spirits returned to the origin of life. The moon was also used as a guide for planting and fishing. “The process from idea to image is interactive and ongoing,” says von Bassewitz. "The lines of the taniwha and around them develop their own life, metaphorically dancing between the spiritual and the physical world, constantly tilting and shifting. Mine is a perspective of 'time,' rather than geometry or pictorial depth. In 'time' everything is connected although constantly changing—this is a fundamental of Maori identity and ideology." Noa Noa von Bassewitz addresses this shifting connectedness through her taniwha and demonstrates that they are more than supple shape-changers. Their light and dark aspects are part of a rich cultural psyche and identity, and myths associated with taniwha, and with the moon, prevalent throughout the Pacific Rim. But, as von Bassewitz demonstrates, their symbolic significance is wide and ongoing. In the Maori world, the moon is personified as Hinakeha (Pale Hina) and Hina-uri (Dark Hina), the latter name referring to her absence during the hina-pouri (the dark nights) when she is said to go on long sea voyages. These voyages (of self-discovery?) are alluded to in Taniwah and Moon under a Microscope (2009). This is a series of vignettes, male and female taniwha shift and swirl, each set against their own backdrop of moon and seas. The work, von Bassewitz says, is an exploration of the complexities of self and the endless possibilities of pattern and growth; it is an exploration of not only these mythical shape-changers, taniwha, but also the flux of individual consciousness in contemporary communities. A more lyric surge sweeps through the lines and colors of Moon Lovers, Taken in the Moonlight, and By the light of the Moon. As their titles suggest, these forms conjure up passionate encounters. But, as in the drawings of children, neither time nor space has any significance here. The artist 's imagination and myth co-exist. Yet, if this suggests a harmonious simplicity, then it also conceals a number of breaks with pictorial traditions. Unaffected by plays of perspective or the force of gravity, the 'reality' of these works lies elsewhere. Concrete ideas may be alluded to, as in Oh Mama and 60 Backwards (both 2009), but these are subsumed into symbolic energies and promptings, in bold colors and attenuated, wiry lines. Oh Mama is a strong and nurturing print. Against a sunburst of radiating lines, the large and small entities fold gently into one another evoking comfort and protection. And 60 Backwards considers a pivotal year in an individual's life. As the title suggests, 60 is an age that is often graced with hindsight and, therefore, an increased awareness of the value of life. If Desert Taniwhess (2009) is read as a red oval of gathering energy, womblike, then Cavorting Taniwha (2009) positively exudes bacchanalia rejoicing- everywhere is movement and old gold light. They may well be the taniwha believed responsible for the eruption of Ruapehu, Ngauruhoe, and Tongariro; the volcanic aftermath creating the Rangipo Desert. Overall, there is the suggestion that the physical world and the spiritual world of whakapapa (community and ancestors) are closely related-that we are all part of a universal energy. Von Bassewitz's taniwha are primal yet strangely familiar—they bring the te ira atua (the godly or mythical aspect) into contact with the light and dark in te ira tangata (the human aspect) and she does so with a creative agility reminiscent of whahairo rakau—the ancient art of carving. According to this time-honored practice, a tohunga whakairo (a master carver, traditionally male) would accept a specific commission with a defined purpose and boundaries. It might be for a waharoa (gateway) or kaitiaki (guardian figures) for a wharenui (meeting house) or pouwhenua (marker posts). Having addressed the specifics, however, the carver was then free to elaborate up on them to create highly original works—not just replicas or versions of other works. In this sense Maori art, albeit sourced in an ancient tradition, was and remains everevolving, never static or mere repetitions of precedents. Von Bassewitz's sculpted woodblocks follow in this creatively independent line, the whahairo rakau. Her gouged lines draw upon the symbolic taniwha entity but extend it as a vehicle for personal invention and expression. "I began the Taniwha and Moon series shortly after a visit to Barcelona in 2008 where I found the work of Gaudi truly inspirational, fuelled by his eclectic passions for nature, religion, and architecture. Gaudi's works are spatial marvels; the plasticity of his undulating lines, the harmonies of colors and materials and metaphor. Having experienced Gaudi's work, I felt charged with enthusiasm, ready to return to my workshop and begin my taniwha works, secure in my belief of the resonance and relevance of myth and metaphor, especially in relation to our contemporary, urban world. "I am an anthropologist by training and inclination and make art gripped by ideas rising out of this. From an anthropological perspective, myths are a great cultural source and can be great celebrations not only of differences, but also of common grounds. "Certain creatures and motifs have collected themselves in my psyche, like a bag of personal yet universal hieroglyphics, such as water (the life source) and taniwha (our light and dark aspects). I draw these out, literally, to express particular feelings and narratives, blending them until they have what I consider to be an authentic Noa Noa look—communications, enquiries, and 'translations'—pared back and refined to their symbolic core. "The medium of the woodblock print, with its plurality and democracy, is well-suited to my art and my aim of sharing things I feel passionately about, such as people, places, and resources. Prints are individual pieces, but they are also multiples-like the oral tradition that carries so much of the Maori culture. "Art for me has always been the product of an emotional state that needs to be explored and creatively expressed in order to be intellectually grasped and understood. The creative process involves not only time for pondering, but also for refining and clarifying—this layered approach, like translation, is necessary if the work is to communicate with others." By rigorously refining her symbolic language, Noa Noa von Bassewitz is able to explore mythical, symbolic depths, which, in effect, tap deep into layers of social, emotional, intellectual, cultural mores, and developments. These layers are complex, connected and ever changing. Von Bassewitz addresses these layers in her shifting taniwha. The result is a body of metaphorical prints moving us between the fluid lines of mythical symbols such as the taniwha and our own changing selves. These works conjure with te ira atua (the godly or mythical aspect) and, by extension, with the light and dark in te ira tangata (the human aspect). Von Bassewitz 's works are bold, affirming that particular symbols, such as the taniwha, are far from extinct or exhausted as an expressive exploration. Taniwha may be grounded in the mists of time yet, as these works attest, they continue as potent symbols and reflections of human culture. Notes:

Dr. Cassandra Fusco is the New Zealand contributing editor for Asian Art News and World Sculpture News. She is based in Christchurch.

0 Comments

|

AuthorJames Gilberd, on behalf of Gilberd Marriott Gallery - a fine arts gallery in Wellington, New Zealand Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed